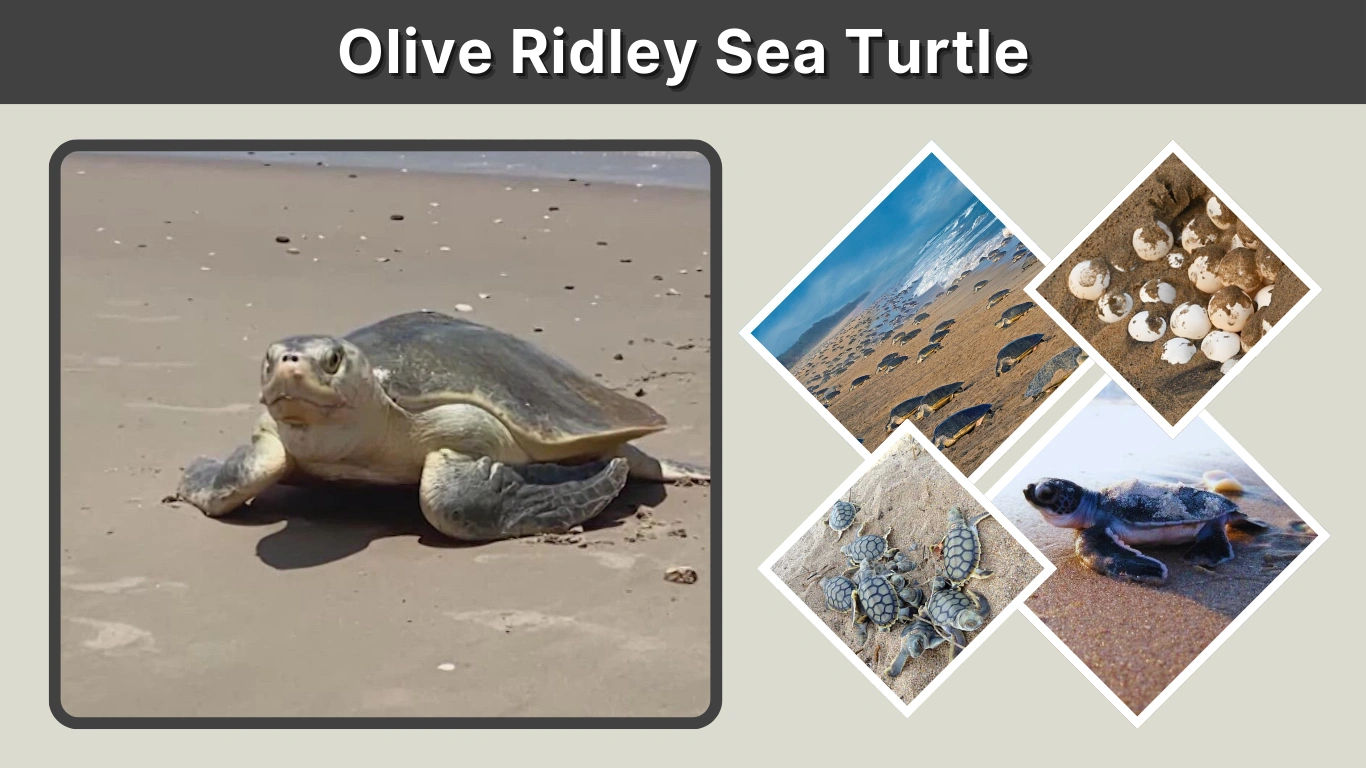

The olive ridley sea turtle is one of the most widely distributed yet still vulnerable sea turtle species in the world. Known for its mass nesting events called arribadas, this turtle plays a crucial ecological role in maintaining ocean health. Its presence across the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic Oceans—especially in India’s Odisha coast and Costa Rica—makes it a globally important species. This article explores its identification, habitat, diet, reproduction, nesting behaviors, adaptations, and early life challenges, offering a complete overview of what makes the olive ridley unique and why its protection is vital.

Overview of the Olive Ridley Sea Turtle

The olive ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) is the most abundant sea turtle species, yet it remains classified as Vulnerable due to threats like bycatch, habitat loss, and egg poaching. The species is named for its olive-colored shell, and its most iconic behavior is the arribada, where thousands of females gather to nest simultaneously on the same beach. These events occur in places such as Gahirmatha and Rushikulya in India, and Ostional in Costa Rica.

Olive ridleys spend much of their life in the open ocean but return to coastal regions during nesting seasons. Their mobility, broad distribution, and mass nesting make them ecologically significant, helping regulate jellyfish populations and contributing to nutrient cycling along coastlines.

Identification, Description & Characteristics

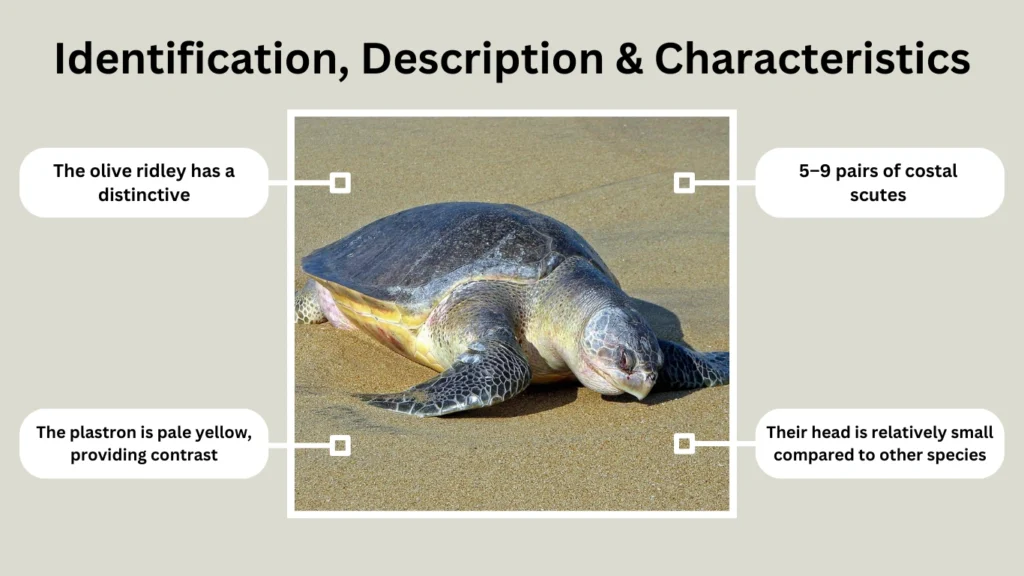

The olive ridley has a distinctive, slightly heart-shaped shell that ranges from olive-green to grayish-green. Adults have a smooth carapace with 5–9 pairs of costal scutes—more than most sea turtle species. Their flippers are powerful, built for long migrations and strong currents. The plastron is pale yellow, providing contrast with the darker carapace.

While juveniles are darker in color and more slender, adults take on the signature olive tone as they mature. Their head is relatively small compared to other species, equipped with jaws strong enough to crush crustaceans and shellfish. When compared with other turtles like the green or hawksbill, olive ridleys are smaller, lighter, and more pelagic in behavior.

Scientific Classification

- Scientific Name: Lepidochelys olivacea

- Family: Cheloniidae

- Genus: Lepidochelys

- Closest Relative: Kemp’s ridley sea turtle

This species belongs to the same genus as the Kemp’s ridley but has a far broader global range, making it one of the most adaptable sea turtles on Earth.

Physical Size, Length & Weight

Adult olive ridleys are among the smaller sea turtles. They typically measure 24–28 inches (62–70 cm) in carapace length. Their streamlined shape enables swift movement through coastal currents and open waters.

Adults weigh between 75–110 pounds (34–50 kg), with females slightly larger than males. Their smooth shell reduces drag while swimming, and the curved edges help them maneuver quickly when hunting small prey or navigating surf zones. Hatchlings measure only about 1.5 inches and weigh less than an ounce when emerging from nests.

Habitat, Range & Geographic Location

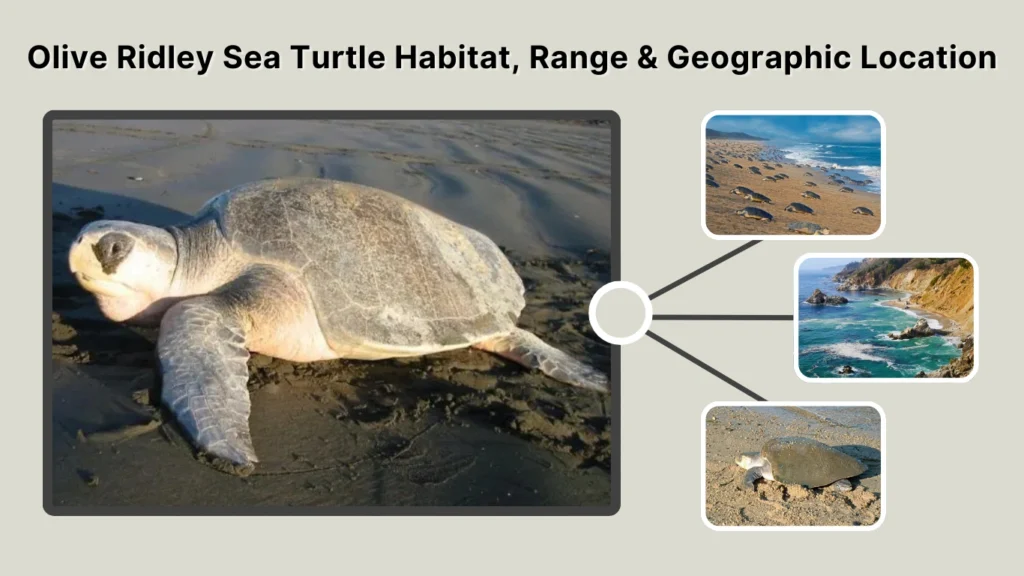

Olive ridleys thrive in tropical and subtropical waters across three major oceans. Their habitats vary greatly depending on life stage. Juveniles spend significant time in the open ocean, drifting in warm currents and feeding on floating organisms. Adults occupy coastal waters, continental shelf zones, and areas rich in crustaceans and jellyfish.

Global Range

They are found across:

- The Indian Ocean — especially India, Sri Lanka, Maldives

- The Pacific Ocean — Mexico, Costa Rica, Peru, Australia

- The Atlantic Ocean — West Africa, Brazil

Key Locations

Some of the world’s most important nesting and feeding areas include:

- Odisha (India) — Gahirmatha, Rushikulya, Devi River mouth

- Costa Rica — Ostional and Nancite arribada beaches

- Mexico — Pacific coast rookeries

- Goa and Chennai (India) — seasonal nesting sites

Habitat Requirements

Olive ridleys prefer warm waters above 20°C (68°F). Nesting beaches must have clean, fine sand; low light pollution; and gentle slopes. Coastal erosion, storms, and temperature changes can drastically impact nesting success, making conservation of these habitats crucial.

Diet, Feeding Behavior & Food Web

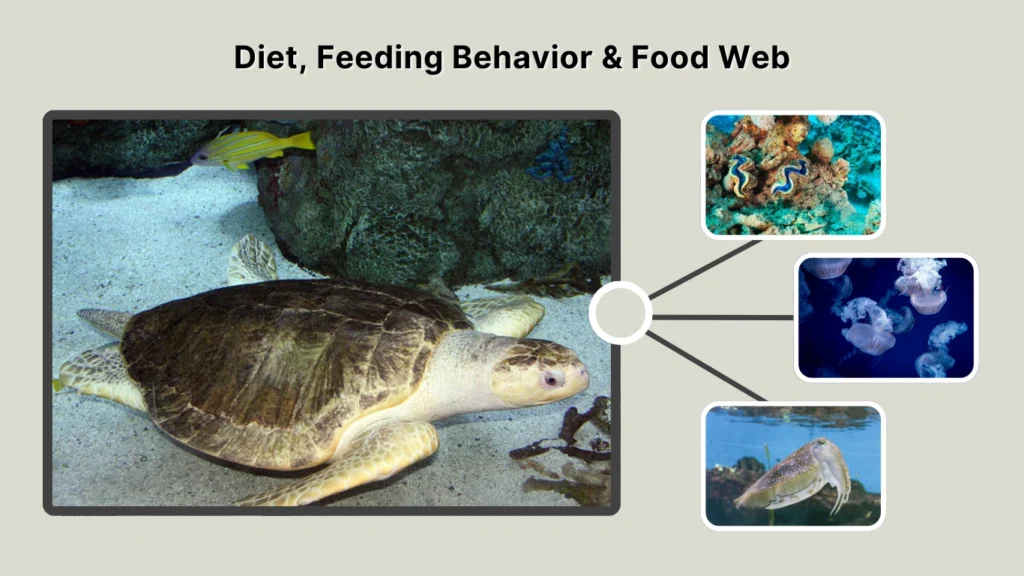

Olive ridleys are omnivorous and highly opportunistic. Their diet is diverse, allowing them to survive in many environments.

What They Eat

They feed on:

- Crabs

- Shrimp

- Jellyfish

- Mollusks

- Small fish

- Sea cucumbers

- Floating algae and plant material (occasional)

This varied diet reduces competition with other turtle species and helps balance local food webs, especially by controlling jellyfish populations.

Feeding Behavior

Adults forage in both coastal and pelagic zones. They use their beak-like jaws to crush shells and capture small prey. While juveniles feed more on floating organisms, adults dive to the ocean floor to hunt crustaceans.

Predators

Natural predators include sharks, large fish, and saltwater crocodiles. Eggs and hatchlings are preyed upon by birds, crabs, jackals, and feral dogs. Human-related threats significantly increase mortality across life stages.

Behavior, Adaptations & Life Cycle

Olive ridleys exhibit several behaviors and adaptations that increase their survival in diverse marine environments.

Daily Behavior

These turtles are generally solitary except during mating and nesting. They spend much of their day swimming, diving, foraging, or resting in warm surface waters.

Key Adaptations

- Olive-colored shell for camouflage

- Hydrodynamic body for long migrations

- Flexible diet for survival in varied habitats

- Mass nesting (arribada) to overwhelm predators

- Temperature-dependent sex determination improving reproductive success in stable climates

Life Cycle

Their life cycle includes:

Egg → Hatchling → Juvenile (pelagic) → Subadult → Adult → Nester.

They reach sexual maturity between 10–15 years, depending on food availability and environmental conditions.

Migration Patterns

Olive ridleys follow warm currents and undertake long migratory journeys between feeding and nesting grounds. Tagging studies show that individuals may travel thousands of miles across ocean basins before returning to natal beaches.

Nesting, Eggs, Arribada & Hatchlings

Nesting is one of the most dramatic and biologically significant aspects of the olive ridley’s life.

Nesting Behavior

They nest either alone or through the extraordinary arribada, where tens of thousands of females come ashore, often over just a few days. These synchronized nesting events occur reliably at certain beaches, especially in India and Costa Rica.

Global Nesting Sites

Major arribada locations include:

- Gahirmatha and Rushikulya (Odisha, India)

- Ostional and Nancite (Costa Rica)

- Mexico’s Pacific Coast

Smaller nesting events occur across the Indian coastline (Goa, Chennai, Andhra Pradesh).

Egg Laying

Females lay 100–120 eggs per clutch and may nest 1–3 times per season. After covering the nest, they return to the sea immediately.

Hatchling Challenges

Hatchlings face extreme predation and disorientation from artificial light. Only 1 in ~1,000 typically survives to adulthood, making nest protection vital for conservation.

Reproduction, Growth & Development

Olive ridleys follow a reproductive cycle shaped by long migrations, predictable breeding seasons, and synchronized nesting. Courtship usually takes place offshore near nesting beaches, where males wait in warm coastal waters for arriving females. Mating occurs in the open sea, often involving multiple males competing for a single female.

Courtship & Mating Behavior

During mating, males grasp the female’s carapace using claws on their front flippers. Females may mate with more than one male, increasing genetic diversity. The reproductive season varies by region but frequently aligns with warmer months, ensuring suitable nesting temperatures.

Embryo Development

After the female lays her eggs, development begins in the buried nest chamber. The embryos grow rapidly during the 45–60 day incubation period, relying on the warmth and oxygen within the sand. Nest temperature determines hatchling sex—cooler nests produce more males, while warmer nests produce more females.

Juvenile Stages

Hatchlings emerge together at night, increasing their collective chances of survival. After reaching the ocean, they enter a pelagic “lost years” stage, drifting with ocean currents and feeding on floating organisms like plankton, tiny crustaceans, jellyfish, and algae.

Age of Maturity

Most olive ridleys reach reproductive maturity between 10–15 years. Once mature, females return to the same region where they hatched, guided by magnetic imprinting that helps them locate their natal beaches.

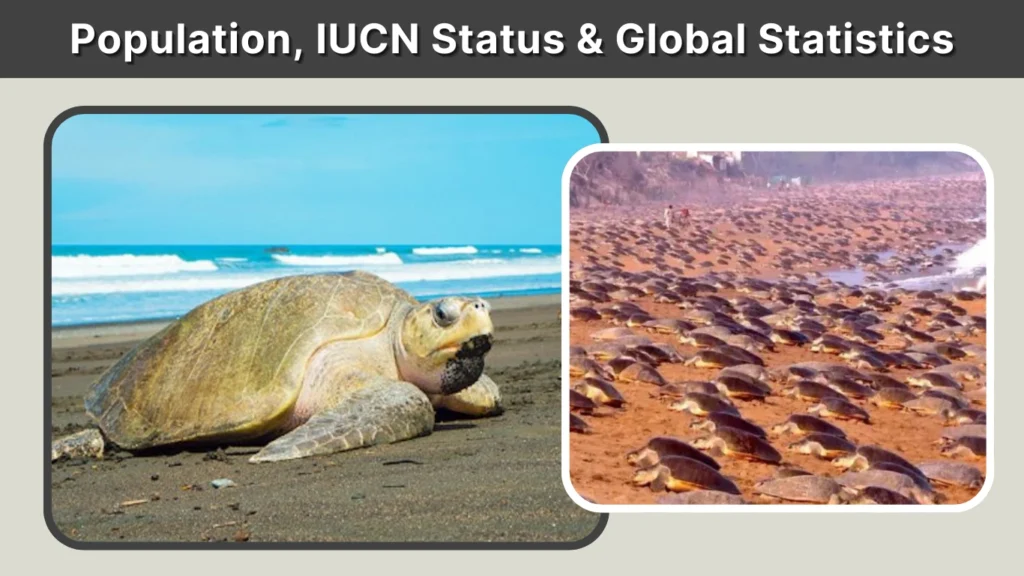

Population, IUCN Status & Global Statistics

Though olive ridleys are the most abundant sea turtle species, their numbers have significantly declined over the last century due to human activities. They are listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List but considered Endangered in several regional assessments where populations have plummeted.

Population Overview

Accurate population numbers are difficult to estimate due to their wide distribution. However, global nesting female populations are believed to be in the hundreds of thousands, with massive fluctuations depending on conservation success, climate shifts, and bycatch rates.

Regional Populations

- India (Odisha) hosts some of the world’s largest arribadas, with hundreds of thousands of females nesting annually.

- Costa Rica supports major arribada sites but has seen periodic declines tied to poaching and poor regulatory enforcement.

- Mexico and Central America maintain moderate nesting populations, though coastal development continues to reduce nesting habitat.

IUCN Conservation Status

The IUCN categorizes olive ridleys as Vulnerable, but their status varies by region:

- Endangered in Mexico and some Pacific populations

- Threatened in India

- Stable but monitored in parts of Central America

This variation reflects how local threats and conservation efforts differ dramatically across the species’ range.

Population Declines

Major declines occurred from the 1950s to early 2000s, when egg harvest, commercial fishing, and lack of protective laws devastated many populations. While global numbers have somewhat stabilized, they remain far below historical levels.

Threats, Conservation Challenges & Protection

Olive ridleys are impacted by numerous threats—some natural, but most caused by human activity. Because they rely on both land and sea habitats, disruptions in either environment can drastically reduce survival rates.

Why Olive Ridleys Are Endangered

Key drivers of population decline include:

- Bycatch in fishing nets, especially in shrimp trawlers

- Coastal development destroying nesting beaches

- Pollution, including plastic bags mistaken for jellyfish

- Climate change, altering sex ratios and beach temperatures

- Egg poaching, a major issue in multiple countries

These threats are amplified by the species’ long reproductive cycle.

Human-Caused Threats

Plastic pollution is particularly dangerous; ingested plastics can block digestion or cause internal injuries. Boat strikes and entanglement in ghost nets also frequently injure or kill adults. Urban lighting near beaches disorients nesting females and hatchlings, leading them inland instead of toward the ocean.

Natural Threats

Predators such as sharks, crocodiles, and large fish pose threats to adults, while hatchlings face danger from birds, crabs, and scavengers. Heavy storms and erosion can destroy entire nesting seasons.

Conservation Efforts

Countries like India, Costa Rica, and Mexico have adopted strong measures to protect olive ridleys:

- Turtle Excluder Devices (TEDs) reduce bycatch in shrimp trawls.

- Protected nesting sanctuaries help preserve key arribada beaches.

- Nest monitoring and relocation programs prevent egg loss.

- Community involvement helps reduce poaching and increase awareness.

International agreements—such as CITES—also help regulate trade in turtle products.

Protected Areas & Reserves

Critical areas include:

- Gahirmatha Marine Sanctuary (India)

- Rushikulya Rookery (India)

- Ostional Wildlife Refuge (Costa Rica)

- Mexican Pacific nesting zones

These reserves combine research, monitoring, and community-based conservation.

Regional Highlights

Olive ridleys are found across dozens of countries, but a few regions stand out due to their massive nesting events and long-term conservation efforts.

Olive Ridleys in India

India’s east coast hosts some of the world’s largest arribadas. Odisha in particular is a global stronghold, with Gahirmatha known as the single largest nesting site for this species. Conservation laws, beach patrols, and community engagement play a major role in protecting nests and reducing mortality.

Olive Ridleys in Costa Rica

Costa Rica’s Pacific coast—especially Ostional and Nancite—supports internationally recognized arribadas. These sites have become critical for scientific study, offering insights into mass nesting behavior, hatchling survival, and threats like poaching and climate pressure.

Olive Ridleys in Mexico & Beyond

Mexico’s Pacific coastline supports significant nesting populations but faces challenges from tourism and development. Smaller but important populations exist in Sri Lanka, Brazil, West Africa, and Southeast Asia, each facing unique regional pressures.

Interesting Facts, Fun Facts & Quick Information

Olive ridleys are full of surprising traits that make them one of the most fascinating sea turtle species.

General Facts

- They are the smallest of the globally abundant sea turtles.

- Their shell is olive-green—hence the name “olive ridley.”

- They lay one of the largest numbers of eggs per clutch among sea turtles.

Fun & Kid-Friendly Facts

- A single arribada can bring over 100,000 turtles to the same beach.

- Hatchlings instinctively move toward the brighter horizon—the ocean.

- Juvenile olive ridleys can drift thousands of miles on ocean currents.

Unique Biological Facts

- Their curved shell reduces drag, helping them swim efficiently.

- They can dive over 500 feet while foraging.

- Temperature determines whether hatchlings become male or female.

Origin of the Name “Olive Ridley”

Their name comes from the olive coloring of their shell and the term “ridley,” which historically described smaller sea turtles with similar shapes.

Species Comparisons

Olive Ridley vs Green Sea Turtle

| Feature | Olive Ridley | Green Sea Turtle |

| Size | Smaller | Much larger |

| Shell Color | Olive-green | Brown to dark green |

| Diet | Omnivore | Mostly herbivore (adults) |

| Nesting | Arribada + solitary | Solitary only |

| Range | Tropical oceans worldwide | Worldwide |

| Threat Status | Vulnerable/Endangered regionally | Endangered |

The olive ridley’s flexibility in diet and habitat helps it survive in more varied environments, while the green sea turtle relies heavily on seagrass ecosystems.

FAQs

Why are olive ridley sea turtles endangered?

They are threatened by fishing nets, egg poaching, pollution, habitat loss, and climate change. Bycatch alone kills thousands each year, making it one of the leading causes of decline.

Where do olive ridley sea turtles live?

They inhabit tropical and subtropical waters of the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic Oceans, with major populations in India, Costa Rica, Mexico, and parts of Southeast Asia.

What do olive ridley sea turtles eat?

They eat crabs, shrimp, jellyfish, small fish, mollusks, sea cucumbers, and occasionally algae—making them one of the most adaptable feeders among sea turtles.

How long do olive ridley sea turtles live?

They can live 50 years or more, depending on environmental stability and threat levels.

How many eggs do olive ridley sea turtles lay?

Each clutch contains 100–120 eggs, and females may nest up to three times in a single season.